On Not Becoming a Tar Pit

I have to choose, when I can, the manner in which I brush up against other people’s lives.

When I was visiting my friend in California a couple years ago, she and I came to the conclusion that one of the many humbling rites of adulthood is realizing that almost every feel-good sentiment conveyed on a corny refrigerator magnet is kind of true. All those dumb motivational clichés about appreciating the little things, having a positive attitude, doing what makes you happy, and treating people kindly—the ones that make me cringe with their corniness—retain a certain sort of wisdom. I still don’t think they make for very good home décor, but I can recognize the kernel of truth at the core of such phrases.

That was my Bad Year, as I’ve alluded to before, and my time in Los Angeles was a reprieve from the angst I was experiencing back home on the other side of the country. I was excited to see my friends, whom I’d known since I was a teenager when every year seemed like a bad year, but I did not expect to like California itself. The truth is that I have never been interested in sports, nor have I ever subscribed to any other form of recreational ideology in which one cohort—particularly a geographical one—is pitted against another for ego's sake. So the imaginary New York/California rivalry that I’ve personally upheld is actually very thrilling to me in its novelty.

Somewhat against my own will, I ended up enjoying Los Angeles. I maintain that this was due almost entirely to the company I kept while there, but I nevertheless allowed myself to take pleasure in the new landscapes, the trees heavy with fruit, the unfamiliar air against my body. I was desperate for any comfort, any opportunity for wonderment, any proof that this world was worth its trouble.

Most people I know would agree that living is difficult right now. It seems we are all looking down the barrel of a very large and unavoidable gun at a whole series of Bad Years ahead. It gets harder and harder every day to resist a doomer mindset about the state of society.

These feelings are not unfamiliar, of course.

When I worked as a barista during Covid, pre-vaccine, I developed a powerful loathing for humanity. The café I worked at was in a wealthy, semi-gated neighborhood populated mostly by retirees and young families helmed by tech bros. I had dealt with difficult customers at other jobs, but there was a particular awful absurdity in being verbally abused for not putting enough milk in someone’s coffee while there was still a global pandemic happening and it constantly felt like the world was ending outside. (I was hired after the pots and pans thing had petered out, FYI.) People are fucking dying, I kept thinking. People are dying and we’re technically risking our lives to make you this oat latte and you can’t even look us in the eye when you order it. What’s the point of any of this?

The customers’ entitlement and condescension, their disregard for the safety of my coworkers and myself—it all seemed neverending. Although I disliked working there for a lot of reasons, the primary one was that it resulted in my feeling hateful toward people in general even after I left the café at the end of my shift.

I did not relish feeling this way. I did not like the resentment that festered within me during the months I worked there, how that sense of singularity made me isolate myself further in a time when we were already so isolated from each other. My attitude was basically: the only person I could count on is myself, and fuck everybody else.

This is no way to go through life. After all, we’re living in a society here.

Occasionally customers were nice—they complimented me on my earrings1, sincerely wished us a good day, remembered our names, tipped extra for no real reason. Those interactions were usually enough to power me through at least another hour on shift. When I have a pleasant interaction with a stranger, it similarly buoys up my mood for the rest of the day. Depending on the level of pleasantness, it can improve my outlook on the world for the rest of the week. Even if the afterglow only lasts a few minutes, that feeling of relief is often profound. At the very least it takes my mind off whatever horrible headline just popped up on my phone.

Since the election, I have been making a conscious effort to have at least one truly pleasant interaction with a person every day. I try to be heartfelt when I ask people how they’re doing. I compliment people on their shoes and earrings. I help people with directions. People tend to respond in kind. Even when it’s not a direct interaction I try to stay attuned to the gentle human acts around me and elevate them in my memory above other daily annoyances and disappointments: a father patiently answering his daughter’s barrage of questions on the subway; two strangers exclaiming over their matching bags; a person bopping their head along to the song playing in a bookstore and the cashier catching it and smiling to herself, proud of her playlist. How lucky am I to live in a place that allows me to witness these moments, so lovely and inconsequential?

I have to believe in the goodness of both myself and other people in order to survive. For my own sake, I have to prove this potential for honest human connection. I have to believe it is within my power to not contribute to the collective misery. I hesitate to think of it as altruism, because I am motivated by a desire to make myself feel better about being alive.

I do not believe in any great spiritual interconnectedness, or the push and pull of “good” vs. “bad” energy or vibes or karma or whatever. In these cases, I believe in simple cause and effect: when you are nice to someone, they are almost always glad, and when everything seems so unbearably awful all the time, that gladness is worth sharing, even just for a moment.

I don’t mean for this to sound self-righteous or reductive when it comes to the world’s most pressing issues. I know that small gestures of kindness are not going to be society’s sole salvation, and I know that structural change will only come as a result of broader, organized action among many participants.2 I also know that more material gestures of help and solidarity (i.e. giving money to people who need it) are just as important as daily politenesses—probably even more so. But we will still always have to contend with the everyday, the micro-est of micro-interactions that come as a result of living in a world that contains other people.

In other words, my grand conclusion is something you would find on one of those corny magnets: 𝓫𝓮 𝓴𝓲𝓷𝓭.

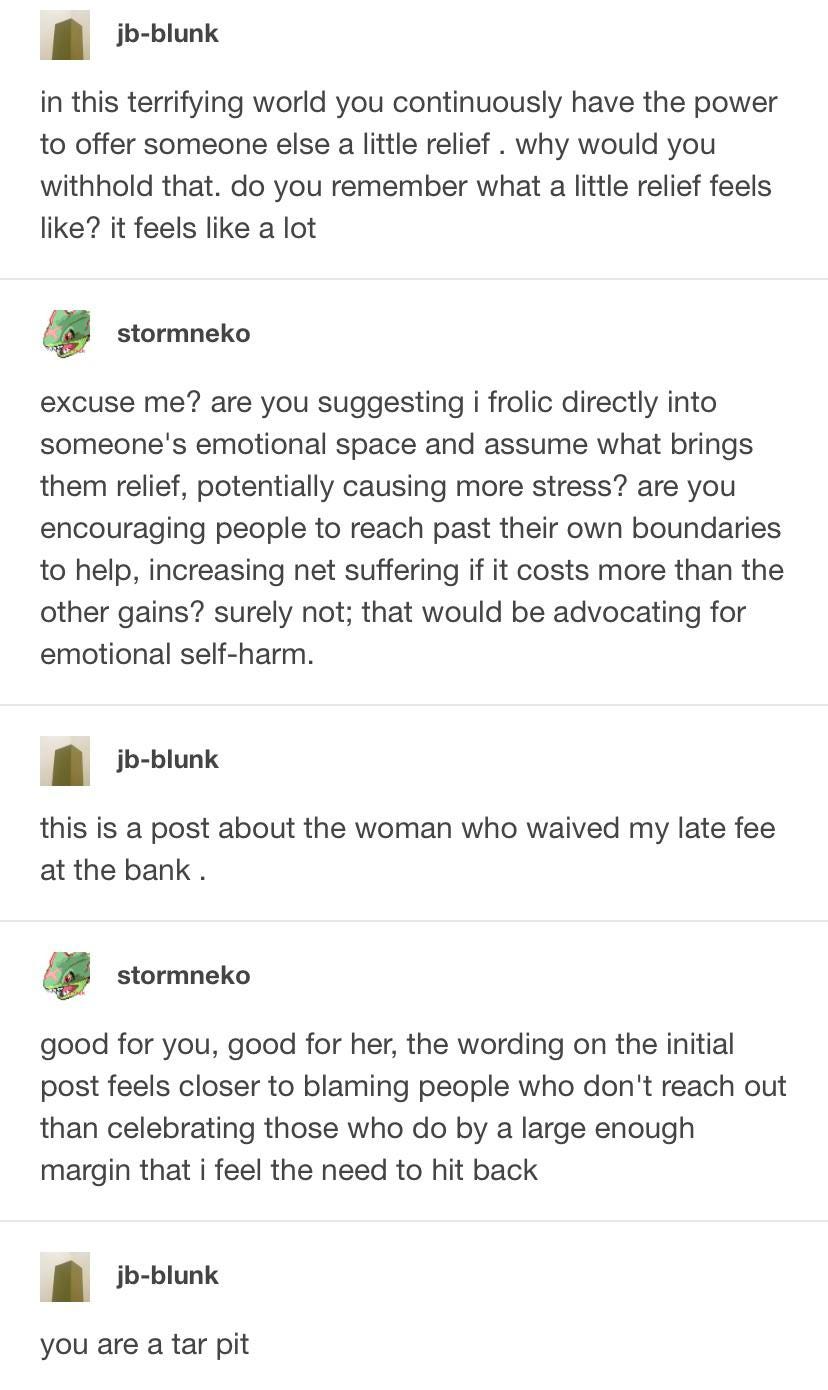

The source of this entry’s title is the pictured interaction between two online strangers from a couple of years ago3. A tar pit is a fissure in the earth in which long-buried crude oil bubbles up to the surface; once caught in the hot, sludgy natural asphalt, animals (or anything else) are unlikely to escape. Though it’s only 15 feet deep, the most famous of the La Brea Tar Pits in California has yielded millions of fossils dating back to the Ice Age. The Pits still pose a hazard to wildlife today, and to rescue anything from a tar pit is a precarious, often futile process.

The memorable statement that closes this conversation is so devastating in its acuity that it’s easy to overlook the original post, which I think is just as succinct and effective. Why would you ever withhold a little relief, so easily given? In some ways my attitude during my time as a barista holds true today: the only person I can count on is myself. So I have to choose, when I can, the manner in which I brush up against other people’s lives.

The feeling I associate most strongly with that week in Los Angeles is relief. I can still access it now if I think about it hard enough, a sense of something warm and vital welling up inside of me where there had previously been a desperately empty cavity. The sun was hot just as I dreaded, but the breeze came in clear and sweet through the open windows and for a few days I was perfectly at ease. Now I don’t hate California after all…and I would actually like to see the La Brea Tar Pits, so I guess I’ll have to return at some point anyway.

— ECT

This was the only part of my appearance that they could comment on anyway, since I was wearing a mask and a compulsory uniform that bore a striking resemblance to that of a early 20th century train conductor, or perhaps an ensemble member in a middle school production of Newsies. I got a lot of use out of my novelty statement earrings that year.

I also know that the despair that I experienced as a barista during the pandemic pales in comparison to what healthcare workers and other actually essential workers went through during the same time.

I have to assume the person in the screenshot is not the real JB Blunk.