The Andy Warhol Enjoyer Has Logged On

Warhol's films are seamful rather than seamless in their editing, rife with the evidence of human touch.

It’s a tired cliché but there is nevertheless an element of truth in it: Andy Warhol was Andy Warhol’s best work of art.

Warhol has become so ubiquitous as to become invisible, much like the subjects of his most famous artworks. Part of what made his paintings of Coca-Cola bottles and Campbell’s soup cans so arresting was the very notion that he had painted them at all—that is, that he had looked at these banal, low-brow fixtures of everyday life with enough curiosity and affection to commit them to paper, over and over again. As if they were worth something. As if they were beautiful.

Today, Warhol is just like any other mass-produced consumer good with no personality or meaning beyond a recognizable name, logo, shape, and/or color scheme. Outside of auction houses, Warhol’s cultural presence has gone from the realm of high art to low art because of how successful—and therefore commonplace—it is. It’s so easy to dismiss. It’s superficial, it’s boring, it’s been discussed to death, and Warhol was an asshole anyway, so who cares? The narrative is simple: Warhol wanted to be a brand. He wanted to be a machine. He wanted to be a non-human commercial entity, and that’s what he achieved.

Last spring this image kept floating around my online spaces, to my immense consternation:

Warhol seemingly falling out of favor with the public and my own mile-wide contrarian streak have resulted in a strange impulse to defend him, or to at least consider him seriously while everybody else is dunking on him. I was irritated by this image because it is remarkably untrue. Despite its prevailing association with artifice, Warhol’s work was grounded in the actual, not the artificial. He loved things, loved them enough to preserve them forever in his paintings and photography and also quite literally in the boxes and boxes of ephemera (others might call it trash) that he collected over the course of his lifetime. As Olivia Laing writes in The Lonely City, the book that singlehandedly changed my mind about Warhol as an artist,

“…[P]art of the reason Pop Art caused such enormous hostility…is that it looked on first glance like a category error, a painful collapse of the seemingly unquestionable boundary between high and low culture; good taste and bad. But the questions Warhol was asking with his new work run far deeper than any crude attempt at shock or defiance. He was painting things to which he was sentimentally attached, even loved; objects whose value derives not because they're rare or individual but because they are reliably the same.”

He pursued sameness even with the moving image: his infamous early films are basically endurance tests of varying lengths for the audience. Very little occurs in them. It’s uncomfortable to sit and watch someone sleep for over five hours, or eat a mushroom / receive oral sex for for thirty minutes straight.1 These films are monotonous; in Sleep (1964), for example, Warhol and his editor Sarah Dalton strove to excise as much natural variance in motion (twitches, sighs, etc.) as possible. He wanted it to be projected at twice the frame rate of the original recording, so all this non-movement would be drawn out even further. The camera angle changes, but nothing actually happens. Monotony was the goal.

I think these films are even more interesting in our current age, when people (myself included) admit to getting antsy after watching even a few minutes of TV without picking up their phone to poke at simultaneously. They’re more challenging today not because of their intimacy—we are no longer shocked or discomfited by the imagery of a total stranger doing something as private as sleeping or snacking or getting a blowjob, because millions of videos featuring these subjects are readily available online—but because they are so damn long and so damn uneventful. They are the perfect antithesis to the flashy, loud, ultra-condensed video sponcon that has flooded the internet and effectively sidelined all other forms of content in recent years.

In his real-time commentary on Sleep, critic / professional Warhol enthusiast Blake Gopnik notes that he’s “glad [he] didn’t ask for the WiFi code for the gallery. The 21st century permits distractions and multitasking that the 1960s didn’t. Does that make us feel even more stranded in Giorno’s sleep, since we aren’t used to EVER surrendering to one stimulus?” I like this phrasing a lot, all that sibilant alliteration, the insistent shh, appropriate for a cinema or a nap or another designated quiet environment. I like the idea of surrendering to a film, slipping into it somehow and losing yourself in the process.

David Schwartz, the Museum of the Moving Image’s curator-at-large, makes a similar observation in his essay for Reverse Shot: “[M]ost Americans spend more than twice [Sleep’s] running time per day looking at screens; the five plus hours don’t actually feel like such a demand.” I would argue that the run time does feel like a demand still, an almost excruciating one in the eyes of most people today, and the film is all the more compelling as a result.

I find it hard to think of Warhol as superficial when presented with such works as these because they are so human, both in the plainness of their subject matter and in how much they manage to fail at monotony despite that being their express goal. Warhol was not particularly skilled with the camera on a technical level at this point (it was a recent purchase). The exposure and white balance fluctuates, the image wobbles in and out of focus, the sutures between shots are obvious and make no effort to conceal themselves via conventional continuity editing. It is seamful rather than seamless, rife with the evidence of human touch.

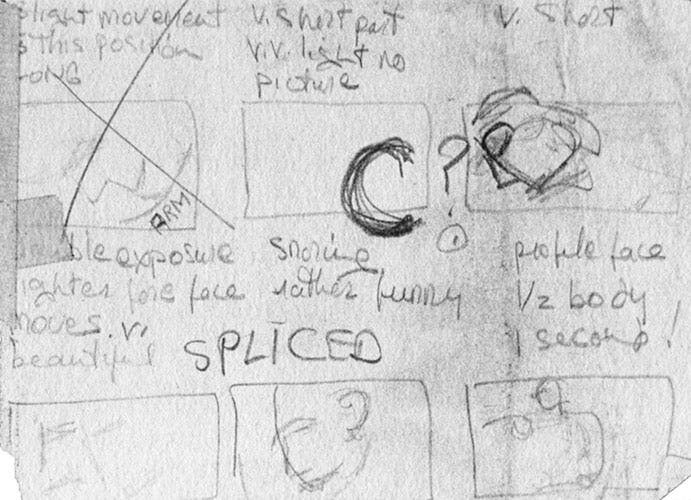

Nor does it strike me as lazy. In fact it seems grueling to sit and record someone sleeping for any amount of time without losing interest, and then to review the thousands of feet of film, edit out any significant motion, and splice it back together again. Dalton even made storyboards to organize the shots according to some inscrutable, non-chronological logic. Warhol spent months filming Sleep in 3-minute intervals during the summer of 1963. It must have been stiflingly hot, as many New York summers are. There must have been a fan on somewhere in the apartment that remained unrecorded by the silent footage. He must have been sweating, uncomfortable, perhaps craving the very same sort of rest he was capturing on his new Bolex 16mm.2

In short, it was a huge commitment. As such, the film feels like an extraordinarily loving, almost worshipful act—and indeed the somnolent subject of Sleep is John Giorno, a poet and Warhol’s lover at the time.3 But even disregarding the sleeper’s identity, the film transmits a profound sense of appreciation for the mundane non-activity of rest because of how carefully and attentively it has been captured. (Aren’t they the same thing, love and attention?) It’s boring, yes, but boring is not so distinct from meditative or peaceful.

Ultimately, I think it’s pretty useless to speculate as to how a historical figure might have responded to contemporary technology or political events because it’s almost always based on pure projection. So I don’t really care to wonder if Warhol would have loved AI, or if Keith Haring would have embraced NFTs, or any other shallow hypothetical that ultimately serves to only reinforce the most basic understanding of an artist’s legacy rather than consider them as a human being. And I don’t really think Warhol necessarily needs to be defended (yet again)—there exist many valid critiques of his work, politics, and artistic ethos. But I also think it’s curious that the insidiousness of poptimism, which posits that low culture can and should be approached just as critically as high culture, has not affected mainstream ideas about visual art in recent years as it has music and television.

Another Warhol cliché: he loved to look. He was a committed voyeur of both humans and objects. He took inspiration from the subjects he watched and the act of watching itself. In order to appreciate his work, we must also force ourselves to observe the world, including its most commonplace and apparently worthless elements, with as much intensity as he did. We must look, and keep looking. Even if we get bored.

— ECT

In all fairness this was likely not the case, because Warhol was doing a lot of speed at the time.

Giorno is probably best known for his wonderful Dial-A-Poem project, which ran from 1968 to 1970 in its original iteration. They broke up shortly after Sleep was completed, though he and Warhol later revived their relationship in the year before Warhol’s death in 1987.